If Norman Rockwell is any guide to American history, fathers and sons in this country are given to throwing baseballs back and forth, admiring cars together, and talking awkwardly about the birds and the bees.

Father-son scientific team Ted Bergstrom and Carl Bergstrom are a little different. As strong advocates of open sharing of scientific information who have directed their research in part to prove the value of open access to science, the experiences they shared in the natural world, and the ideas about it that they exchanged, created a bond that has not diminished.

Carl, growing up with a father enthusiastic about research, was first exposed to information sharing at home. “I saw the great pleasure that my father took in being a practicing member of the scientific community,” he said. “I heard him exchanging ideas with his colleagues, and from him I got a sense of the joy that came from collaborating with others.”

Once Carl decided to pursue science professionally, Ted’s collaborations took on a more personal cast. “Carl and I didn’t plan on collaborating, we just talk about things that interest us both. As academics, the journal issue was a pressing concern for both of us,” said Ted. “Part of the charm of this subject is that it presents intellectually challenging puzzles along with an important social problem that needs fixing.”

Ted’s groundbreaking, extensive and diverse research tracking journal pricing, and Carl’s studies on alternate methods of assessing the value of scientific information – culminating in the Eigenfactor.org web site – has earned them recognition as SPARC Innovators.

“It’s clear that father and son place a high value on the open sharing of information, and they have devoted their careers to probing the notion of defining value in scholarship,” said SPARC Director Heather Joseph. “Although they work in different fields, they come at the basic questions of fairness and access in ways that will impact scholarly communication for generations. It’s entirely reasonable to believe that, together, they have the ability to change the way journals are measured and purchased.”

Ted and Carl share a compelling family history of activism in scholarly communication. They have made their academic mark in two distinctly different disciplines. Ted, an economist, holds the Aaron and Cherie Raznick Chair of Economics in the Economics Department at the University of California Santa Barbara. Carl, a theoretical and evolutionary biologist, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Biology at the University of Washington.

Though their academic interests diverge, a common philosophy unites them.

“When I think about information sharing, whether it’s in the cells in the body or individuals in a social colony or individuals in an academic setting, I’m thinking about the kind of sharing that has potential to generate public benefits on a large scale and it’s going to work differently than sharing physical resources,” Carl said. “It makes a lot of sense to make sure these societies of cells, or scientists, get the maximum benefit they can.”

Similarly, Ted has long felt that defining the notion of value in scholarship is directly linked to the wide dissemination of that scholarship. As with many scientists, he became aware of the problems plaguing the scientific journal marketplace when he was refereeing journal articles in the late 1990s. He got started “quite by accident,” as he remembers. “I was doing more refereeing than I could possibly do and I needed a way to sort out which journals I’d work for, so I decided on a whim to list them by price per article and work down the list as far as I could go.”

What he found “surprised and infuriated” him.

“The numbers showed that we scholars were being cheated,” he said. The large commercial publishers “were getting free work from us and looting our university budgets.” He says he knew immediately that he had to do something, and as an economist, he felt he could provide useful information if he compiled numbers that would make a compelling case to others. “In the late 1990s, there were a lot of people making speeches about the problem with scholarly publishing, but few were collecting hard statistics.”

The numbers he tracked backed up his impressions. He shared his findings with Carl, who was then a graduate student. “My father first tipped me off to price differences among journals,” he said. “I was already a strong proponent of open source software, and so limited access to research results did not make any sense to me.”

They put their heads together during family visits, over email, and on the phone. They have since collaborated on Ted’s well-known journal pricing web pages, which include data reporting price per article and price per citation for about 5,000 academic journals. (http://www.econ.ucsb.edu/~tedb/Journals/jpricing.html) Carl cites Ted’s influence on and contributions to his Eigenfactor.org web site, which uses the structure of the entire journals network (instead of purely local citation information) to evaluate and rank the importance of journals.

It’s easy to see the influence father and son have had on each other. The Eigenfactor web site draws on data from Ted’s journal pricing research, their main focus of collaboration. And Carl, the biologist, at times speaks like an economist. “Information is fundamentally different from steel or shoes or apples or physical goods,” he explained. “So when we think about social institutions for disseminating and sharing information we don’t need to allow ourselves to be bound by economic conventions that regulate physical goods. One doesn’t want to be naively optimistic and say all information should be disseminated for free to everybody. You can’t do that, and generate appropriate incentives to continue to innovate and come up with new information. If one can provide those incentives, the subsequent problem of distribution doesn’t have to be handled on a pay per receipt basis.”

As for Ted, he’d like to use the data from Carl’s Eigenfactor.org web site to embark on the next phase of their work in the field: making tools that would be useful for libraries to do their journals shopping.

“It seems important that libraries start digging in their heels and refusing to subscribe to overpriced journals, setting explicit limits about how far they’re going to go with spending, and refusing to buy bundles in the form that publishers want to sell them,” he says.

To help libraries evaluate their choices, Ted visualizes creating a tool that would maximize spending based on weighted citations. Once completed, it will allow libraries to type in their budget and receive recommendations on what to buy and what to drop, based on the Eigenfactor citation index or other criteria, such as value per dollar or needs of the discipline.

The new project will be especially useful in the era of bundled journal packages. “It’s hard for libraries to figure out if bundles are better values that individual journals, because there’s often so much in a bundle that libraries won’t ever need,” Ted concedes. “We’re going to help libraries evaluate what’s the better buy.”

Neither Ted nor Carl have felt a career backlash stemming from their strong stance on journal pricing and citation issues. Ted first put his theories into action in the late 1990s, when he decided he wouldn’t referee for or publish in commercial journals. “It was no big sacrifice,” he said. “There are plenty of low-priced journals around, and the society journals are so good it didn’t hurt my career at all.”

“I have always had a strong feeling, from my experience with open source software, that material that’s made publicly available will have more impact,” said Carl. “A strong theme in my early work with my father was that not only is open access in the best interest of science as a whole, it’s in the individual’s best interest to favor nonprofit journals; individuals have their work seen and recognized there. The more I looked at the issue the more it became obvious that there were not high career costs to doing this.”

Other scientists have of course relied on the Thomson ISI citation index for years, and Carl insists that the Eigenfactor system is meant to complement, not replace, traditional means of evaluating journals by putting price in the mix. Still, he believes that the Eigenfactor approach is a better method for the times we live in, giving shifting notions of value.

“As we’ve been looking more at how to talk about what journals are offering good value we’ve become concerned with impact factor as a measure of value,” Carl said. It’s a good rough approximation of citation patterns, but not a good approximator of value. We think we have a better way of doing things, but it will only be adopted if it’s freely available, easy to use, and people see it as an alternative ranking system.” Eigenfactor.org is clearly on this path.

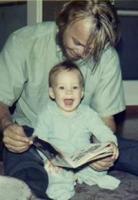

Perhaps the next generation of Bergstroms will contribute their own take on journals when the time comes. Carl’s daughter Helen, 4, already asks to “do science” with her dad. And Helen’s brother, three-month-old Theodore Carl – named for his grandfather – may one day create difficulties for bibliographic indexes. “That would be a lot of fun,” Carl said.

***

Related Links: