Solutions to the world’s most pressing problems require collaboration. How to predict the hazards’ impact and resilience needed for an earthquake is one of those looming concerns that is best addressed with coordinated resources, transparency, and partnerships.

The Cascadia Region Earthquake Science Center (CRESCENT) is embracing this approach and leveraging open practices to connect earthquake scientists and practitioners who respond to natural disasters.

Diego Melgar, geoscientist and director of CRESCENT

In 2023, the National Science Foundation gave a $15 million grant over five years to establish and fund CRESCENT, a research coordination network based at the University of Oregon. The center is the nexus for earthquake science and hazards research, helping to bridge what scholars are learning at 14 universities and the needs of emergency managers, planners, policymakers, and engineers on the ground.

“The mission is to advance earthquake science with the ultimate goal of increasing regional resilience to earthquake hazards,” said Diego Melgar, a geoscientist and director of CRESCENT. “We have between 50 and 80 researchers involved and the job of our staff of six is to keep everybody informed and coordinated.”

While people often think of California as being at risk for earthquakes, scientists are eager to better understand the Cascadia Subduction Zone (CSZ). Subduction zones occur where two tectonic plates are crashing into each other, often causing the world’s biggest earthquakes. The NSF is investing in the center to advance the scientific understanding of this critical zone, to prepare responders, and improve public awareness of the earthquake threat.

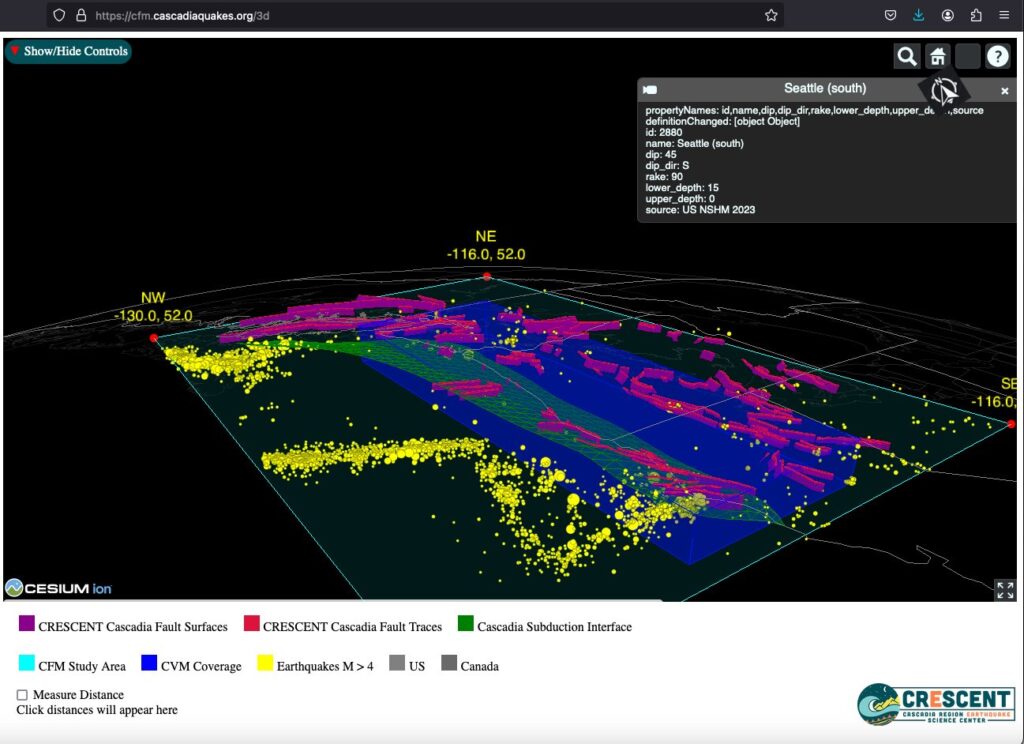

Screen image showing CRESCENT’s open online data viewers for Community Fault Model

Scholars in the earth sciences have been at the forefront of open science, adopting open standards and promoting open data sharing for more than two decades. “Part of the culture of the field is that if you deploy sensors to collect data, if it’s funded by NASA or any federal agency, it is understood that it is going to be open and available to everyone to pick it apart. We can have more gains because more brains are looking at it,” Melgar said.

Still, Melgar added, many individual investigators work on their own individual projects and do not communicate with practitioners, so a clearinghouse was needed.

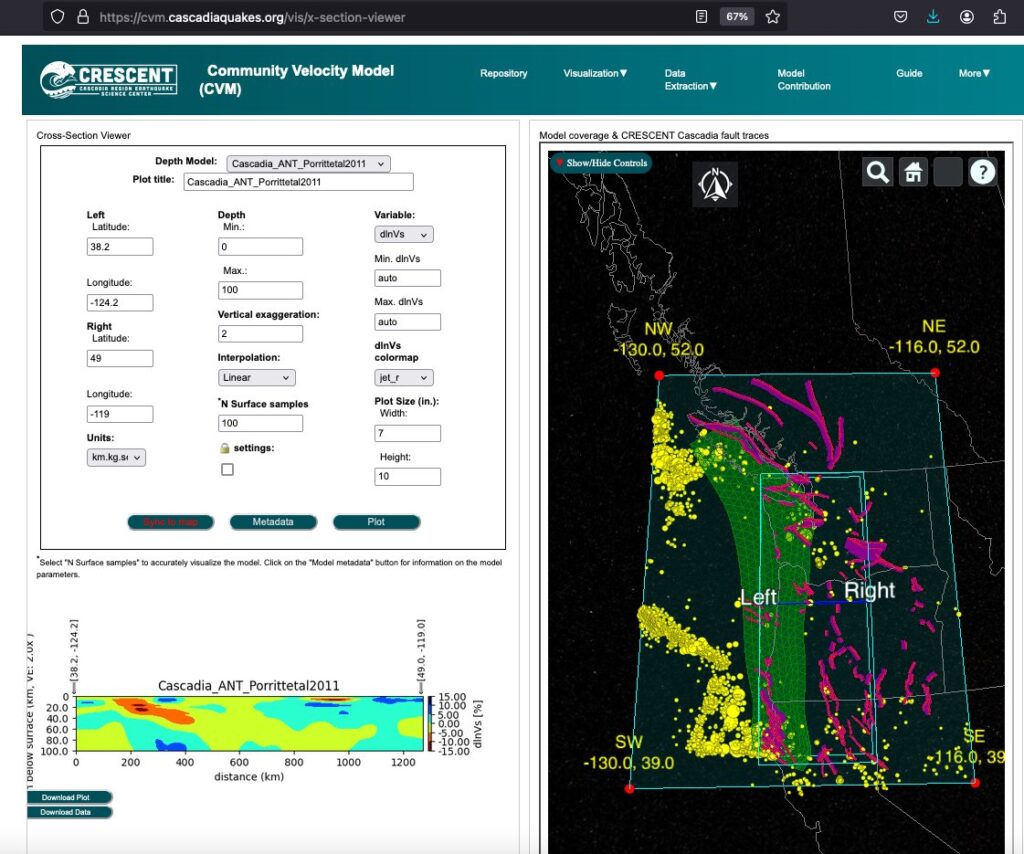

Experts at CRESCENT are creating systems and open tools to keep researchers informed. For example, one working group is building a verification platform for researchers to upload results and models of earthquake ruptures. Another group is building a database of microfossils for geologists to look at each other’s samples. The center is supported by dedicated developers and a cyberinfrastructure designed according to Findable, Accessible, Interoperable and Reusable (FAIR) principles.

Screen image showing CRESCENT’s open online data viewers for Community Velocity Model

“The goal is to get researchers to communally share their findings so that we can cross compare—so we don’t just have the lone genius producing the best model,” he said. “It’s actually more of a collective effort.”

The center offers tutorials on open-science notebooks such as Jupyter, hosts a message board to foster communication, and requires preprints to be posted of all papers funded by the center. Earth science researchers developed their own preprint server, EarthArXiv. “It is part of our culture to preprint ahead of submission,” Melgar said.

There are also open-access journals that have been launched recently in the field including Seismica and Volcanica.

Cover photo for the Seismica special edition

“They’re entirely community run and wildly successful,” Melgar said. “People are eschewing the idea of paying $5000 [for an APC] to publish. There’s a bit of revolt going on in our field where people are realizing maybe that’s not the best model to share research, especially if we want to be good stewards of taxpayer dollars.”

For the interns and undergraduates working with CRESCENT, open science is just the default—the obvious way of operating, Melgar added.

One of the most impactful initiatives of CRESCENT in its first year of operation was hosting a partners meeting in Portland, Oregon. Scientists, representatives from agencies that produce hazard information, practitioners, and private and public stakeholders were able to hear from each other and engage in dialogue.

“We want to connect research to the partners who have mandates to take action to prepare for earthquakes, to increase social resilience,” Melgar said. A feedback loop has been established between researchers and practitioners on the latest findings and what kind of information is useful for agencies.

“There’s no reason to let fear be in the driver’s seat. Science can help. Technology can help,” Melgar said “We know about earthquakes now, and we know what we need to do. We just need to get it done.”

#